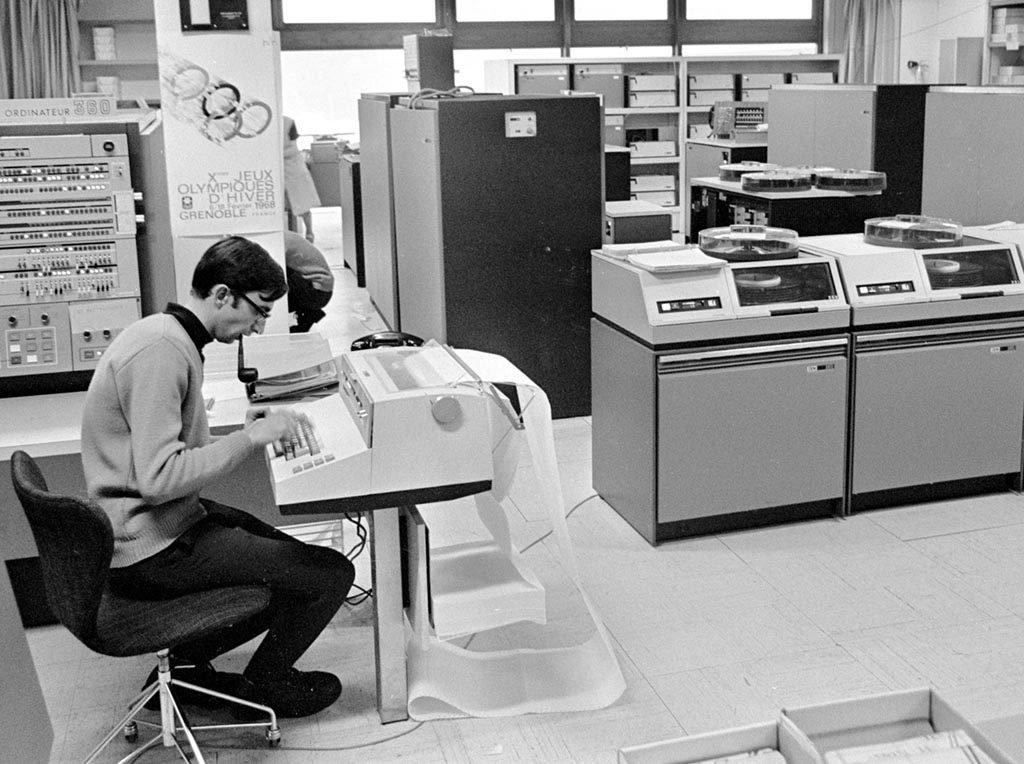

Passwords were first used in the 1960s by early computer users that were largely academics and specialists.

There weren’t nearly as many sets of account credentials to remember back then, and there weren’t as many cybercriminals around the world at that time trying to gain illicit access to them.

Systems in those days weren’t attached to global networks. This—combined with the rarified levels of knowledge required to operate them—meant an obscurity conducive to security and a particular sort of irrelevance for user experience concerns.

Today, on the other hand, billions global citizens live and work in the digital world. Users need to access dozens or even hundreds of personal and business accounts, leaving the average employee to keep track of an astonishing 191 passwords.

Passwords, Smartphones, and Legacy MFA

Unfortunately, all of these passwords are still best suited to the world of computing obscurity—not to the world of continuous global access.

Password-based authentication is “point-in-time” authentication. It asks users to confirm their identity once, at the beginning of a session—and then leaves them to it. This even though connections and sessions can be hijacked at any time. Even though anyone that happens to arrive at an unguarded-yet-logged-in workstation can now mine its data and capabilities easily with modern user interfaces.

Login time-outs and re-authentication prompts throughout the day have gone some way to ensuring that any logged in “Tom” remains “Tom.” Even so, if a black hat has secured a stolen password, it’s no significant obstacle to enter it again—and again—whenever prompted to do so.

Multi-factor authentication (MFA) attempts to solve this problem by asking for several forms of identification together. When new, it was the province of governments, militaries, and specialized hardware. Since today every “Tom” now carries a smartphone, however, a variety of aging phone-based MFA solutions are increasingly imagined to be the cure for the world’s authentication problems.

Today’s Toms are thus prompted, after entering their passwords, to also authenticate using their smartphone. They usually do this either with an app or an SMS code, delivering temporary credentials that change regularly and are valid only for brief periods of time. This is presumed not just to be a best practice, but to be a best-possible practice. It isn’t.

Why Legacy MFA Isn’t Enough

Technology and authentication practices have evolved—but attackers have, too.

SMS messages—sent using an aging, archaic infrastructure—are no longer difficult to intercept. Phones themselves, which today run a variety of operating systems and versions, can be stolen and often cracked.

“MFA” is thus often shorthand not only for new, highly secure technologies, but also for a variety of less secure legacy ones that rely on commonplace communication systems and everyday smartphones. Too often, these are easily compromised.

Worse, in today’s typical MFA case—a known username, the correct password, and a matching device—the identity of the user still can’t be confirmed. All that’s certain is that the user at the other end of the session possesses the right things—not that they actually are who they claim to be.

Is this really Tom, in other words, or does someone else have Tom’s credentials and smartphone for some reason?

And Neither Is Policy Strictness

The proliferation of authentication prompts and matching passwords means worse passwords. We know this. When users have a hundred or more to remember, it’s not hard to see why “password” and “123456” end up authenticating their sessions.

But when paranoia about password and smartphone-based MFA weaknesses lead to more draconian authentication policies, more security is not the result.

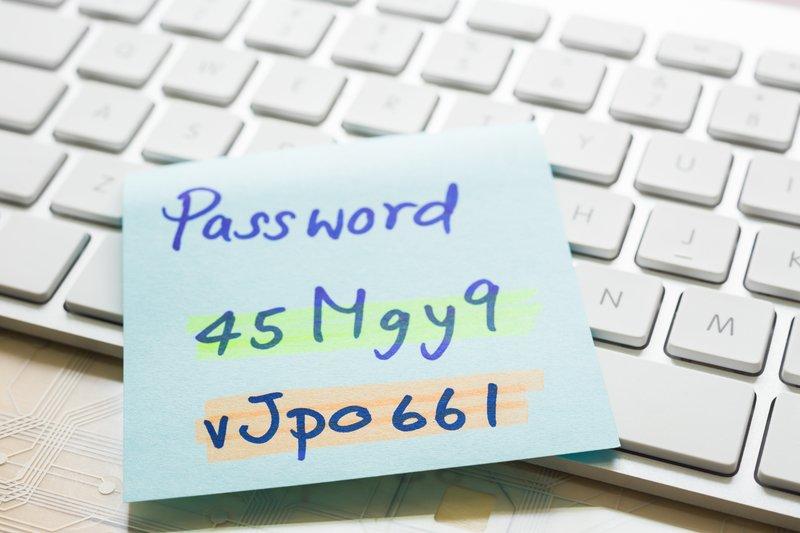

Elaborate password character rules and frequent password expiration lead users to simply do whatever is necessary—first to get the system to accept their latest password, and second, to remember it.

This means iterated passwords like “C4$hman1” followed by “C4$hman2” followed by “C4$hman3″—all easy cracking for an automated attack. Of course, the attack itself is unnecessary when frustrated users simply write their passwords on post-it notes.

Meanwhile, the inconvenience of having to check a phone for each login leads users to configure their SMS clients in insecure ways. For example, they often set messages to appear as notifications on their lock screens, eliminating any benefit the SMS code may have provided.

Users bristle even more at the need for corporate control of devices. They balk, then install roots to bypass them, then install hide-roots to disguise their activity. The result? A spaghetti mess of unaudited gray- or black-hat code. All of this on devices supposedly used for security and authentication purposes.

Legacy MFA tools simply aren’t adequately protecting the billions of critical systems in banking, energy, infrastructure, government, health care, education, and business.

More of our society is wrapped up in technology in more ways than ever before. We need more from our authentication systems.

Continuous Authentication Really Is a Thing—the Right Thing

What’s needed is a way to continuously authenticate users—not just at one point in time, but all the time, as they work—and to do it without requiring them to remember things, possess things, or otherwise make space in their already busy minds and schedules for security tasks that just aren’t their job.

It always gets us at Plurilock™ when people are surprised that this technology exists. In fact, it’s more than a decade old at this point.

Yes, continuous authentication without passwords and smartphones is a thing.

It can identify who someone is—not just that they “have the right things” in their mind and in their hand—and it can do so all the time, without bothering them. It’s what we sell.

Now we’re not asking anyone to get rid of passwords. They’re easy to implement, broadly understood, convenient, and one more identity factor that can be brought to bear in an authentication situation.

What we are suggesting is that we stop trying to burden passwords and smartphones with the task of holding up the entire security edifice of today’s global society.

They just weren’t designed for that.

And frankly, when placed into that position, they suck at it.

What Authentication Should Look Like Today

Here’s what an advanced, continuous authentication solution should look like today:

-

When Tom logs into his system in the morning, it recognizes him—the actual person and body—and continuously verifies that actual person and body throughout his entire workday.

-

Even if Tom has a weak password or steps away without logging out, no one else can pretend to be him, because the system will recognize that it’s the wrong person and body right away.

-

If Tom does something weird or out of character that throws his identity into doubt, he’s blocked right away—but if he’s able to deliver enough trusted proof of identity in other forms, he can be allowed to compute again.

-

The identity data stored about Tom can’t be re-used to impersonate him, even if it’s stolen, either on the same system or on other systems. If stolen, Tom’s identity data is all but useless to the thief.

-

Tom himself can’t secretly deliver or sell his identity data to bad actors, either. No one can get a cooperative Tom in a room for five minutes and capture the ability to impersonate him to secured systems.

-

All of this is done without Tom having to become a security expert, or even having to know about it; the system does what systems do—compute, including about Tom’s identity—and Tom does what he does, rather than fumbling around with password requirements and security devices all the time.

If you think this sounds amazing, you’re not alone. We hear this excitement all the time when we demo our technology for delighted future clients.

Continuous Authentication Is the Future

For these reasons—it’s a desperately needed technology, and it’s one that exists and is rolling out everywhere—we’re sure that continuous authentication will supersede password-based authentication and legacy, phone-based MFA technologies as the first line of defense in months and years to come.

After all, passwords date to the ’60s. Mobile phones date to the ’90s. But we’re not living in the twentieth century any longer. The time for widespread continuous authentication has come. ■